The tale of a princess who disturbs an aged sage’s meditation has universal resonance. Ravi Shankar was drawn to the story, seeing perhaps an echo of his own. His opera Sukanya (meaning ‘a beautiful girl’) receives its première this May. Ken Hunt gives us the background and context.

The starting-point of Pandit Ravi Shankar’s only opera Sukanya is a minor tale in the Mahābhārata, idiomatically, ‘great tale of the Bhārata [dynasty]’. Musically worked up from Shankar’s musical sketches and verbal steers and realised by David Murphy, its librettist Amit Chaudhuri is the very person to treat myth as malleable raw material rather than immutable certainty when realising Shankar’s vision. The Panditji of my acquaintanceship would have approved. After all, milking and, indeed, churning myths or traditional folktales for stories or plots is the common currency of opera. Transferred tales of brave Orpheus, for example, touched opera, notably Claudio Monteverdi and librettist Alessandro Striggio’s L’Orfeo, Christoph Willibald Gluck and Ranieri de’ Calzabigi’s Orfeo ed Euridice and Joseph Haydn and Carlo Francesco Badini’s L’anima del filosofo, ossia Orfeo ed Euridice (‘The Soul of the Philosopher, or Orpheus and Euridice’) while, as ‘King Orfeo’, it was seminal enough to rank nineteenth out of hundreds in Francis J. Child’s The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Like these ‘Orpheus outputs’, the Sukanya tale is laced with allegory.

“…Sukanya is not the first opera to draw on Indian antiquity…”

But first, some context… Sukanya is not the first opera to draw on Indian antiquity, nor will it be the last. In the first decade of the twentieth century, the composer Gustav Holst came under India’s spell. In the words of John Warrack’s entry on him in the Dictionary of National Biography, he was ‘drawn to Hindu literature and mysticism’. It could be said that he dipped his toe in the era’s Orientalism but Holst went further and deeper, studying Hindu texts and Sanskrit. Savitri (1908) and Choral Hymns From The Rig Veda (1908‒1912) are fruits of this. Yet prior to these works, he had toiled on and off between 1900 and 1906 on an opera called Siva. It never quite flew. In 1985 the London-born composer Colin Matthews, who had worked with the composer’s only daughter, the musician Imogen Holst, wrote: “The opera was never performed, and its libretto is hardly less stilted than the models.” It was of its time and largely without Indian musical references. For example, A.H. Fox Strangways’ benchmark book The Music of Hindoostan wasn’t published until 1914. Holst subsequently dismissed Siva pithily as “good old Wagnerian bawling”. During the 1920s the British composer John Foulds combined opera, Indian music and literature. His Avatara, in the words of Malcolm Macdonald in the notes to the 2004 recording with the Sakari Oramo-conducted City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, was “a mysterious Sanskrit opera […] which he eventually abandoned and destroyed.” Given the combined passion for Indian culture and music of its composer and his vina- and tabla-playing wife Maud MacCarthy, what survived – the three preludes to The Three Mantras– points to a real loss.

“…he slipped into the role of multicultural champion.”

During his lifetime, Ravi Shankar became incontestably one of the four most famous Indians on the planet, not only in the arts and through connections such as George Harrison, but in the world’s wider consciousness. His name was there alongside only Tagore, Gandhi and Nehru. Born Robindra Shankar Chowdhury in April 1920 in Varanasi on the banks of the River Ganges/Ganga in modern-day Uttar Pradesh, he slipped into the role of multicultural champion. That all started early. In November 1930 he was reunited with his extended family in Paris and joined his big brother, the dancer and choreographer Uday Shankar’s Compagnie de Danse et Musique Hindou (‘Company of Indian Dance and Music’), a cultural sensation that travelled as much of the world as steamship and impresario granted.

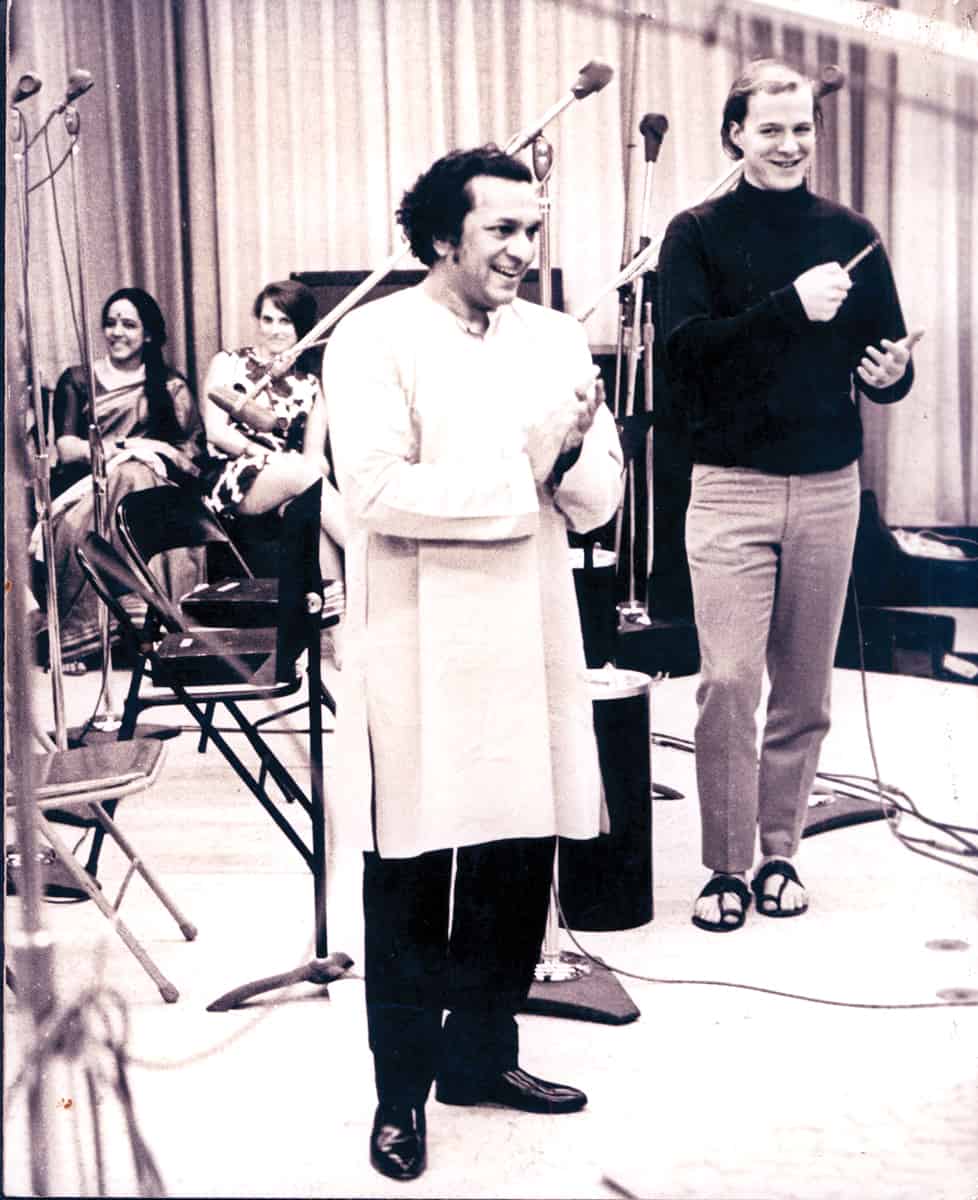

As its most junior member, Robindra ‒ still Robu for short ‒ began observing the incomprehension of Europeans and Americans confounded by the apparent complexity and sheer foreignness of Hindustani classical music. Dare I suggest that learning how to articulate and deliver the music’s melodic and rhythmic structures, traditions and nuances underpinned his life’s work? His experiments with crossover forms are strewn across the decades and in many cases ‘frozen’ as recordings. A sample might include collaborating with Yehudi Menuhin, André Previn, Zubin Mehta or Philip Glass, with the Ravi Shankar Project’s Tana Mana, with David Murphy on Shankar’s Symphony or with tabla maestro supreme Alla Rakha, koto-player Susumu Miyashta and shakuhachi-player Hozan Yamamoto on the, for its time, unique Indo-Japanese collaboration Towards The Rising Sun.

“…Menuhin came across a book on yoga.”

Sukanya was up against an entirely different clock. Begun in earnest in 2011, the countdown to his death in December 2012 was under way. In a manner of speaking, it might be said that Sukanya’s clock started ticking in 1952. Early that year, while on tour in New Zealand, Menuhin came across a book on yoga. Reading it fed a yearning to visit India. Coincidentally, shortly afterwards he received an invitation from Prime Minister Nehru to perform there. That February Menuhin was invited to a house recital held at the Delhi home of Dr Narayana Menon. Performing were Ravi Shankar, his brother-in-law the sarodist Ali Akbar Khan and Chatur Lal (the first tabla pioneer for the wider world). A new era in the history of Northern Indian classical music was about to be ushered in. Not only did Menuhin become a champion supreme of Hindustani music and willingly lent his name to its wider popularisation and appreciation of Indian art music, but it lit the blue touch-paper for West Meets East, Shankar and Menuhin’s ground-breaking East-West classical music collaboration declared Best Chamber Music Performance at the 1968 Grammy ceremonies.

“…an obscure episode in the nebulous Mahābhārata… registered with him.”

On reflection, a more apt year for when the first tile for the Sukanya mosaic was laid might be 1992. That was when an obscure episode in the nebulous Mahābhārata first registered with him. It is one of the principal Hindu epics. Historians and linguists tell us it started life in Sanskrit, only one of the subcontinent’s scholarly linguae francae. It has been translated into a great many languages, into celluloid, digital and television drama and inspired sundry art forms. Shankar connected with it. At the time his mother-in-law Parvati Rajan was staying with him and his wife, Sukanya.

“I’d love to do a ballet…or something.”

“We were in Delhi in the Lodhi Estate house,” says Sukanya Shankar. “Way back in 1992, my mother had come to stay with us for a bit and when she saw me doing things for Raviji she said, ‘I named you right.’ So, Raviji asked, ‘What’s that?’ So, she told him the story about the Sukanya in the Mahābhārat and how this younger princess was married to this older man and how she brought back youth to him. He said, ‘Ah, what a lovely thing! I’d love to do a ballet…’ – he didn’t say opera at that time – ‘…or something.’ We didn’t talk about it afterwards. But he loved the story so much that he’d often say that to me, ‘Your mum named you right.’”

“It is a love story… full of twists, turns, a temptation and a test…”

In Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty’s Other Peoples’ Myths: The Cave of Echoes (Macmillan Publishing, 1988), the tale is distilled as ‘the story of the aged sage, Chyavana, who is rejuvenated so that he could marry a beautiful young girl called Sukanya.’ Amit Chaudhuri’s libretto for Sukanya is no religious tract or folkloric archetype gussied up for sopranos and arias. It is a love story, albeit based on a downright recondite tale. Already full of twists, turns, a temptation and a test of love, its fertile ground includes yogic meditation, an everyday anthill misunderstanding, blinding and rejuvenation. “It’s not a straight love story, no,” its librettist agrees.

“Firstly,” he continues, “it’s a man whose meditation has been disturbed by somebody. He’s been injured by this woman who he ends up marrying and being happy with. It’s a marriage between a young woman and an old man – an old man who’s a sage and a young woman who’s a princess. Secondly, there are competitors who aren’t human beings but demi-gods or whatever who want the woman.”

“It took his mother-in-law…to alert Ravi Shankar…to this story’s existence.”

Culturally, Ravi Shankar was steeped in Bengali culture and Hinduism. (“You know, he might not have known a particular thing,” says his wife, “but he was very well-versed in them and that fed into his knack for writing.”) However, in the north-east of the subcontinent there are oodles of oral and literary traditions including folk-religious tales, verse-narratives and, never forget, the syncretic faith tales in vernacular verse of the Bauls. Some splice together Hindu religious texts like the Mahābhārata and Rig Veda and their folk tale counterparts. Though not an exclusively Bengali example, several concern Manasā, also known as Mansa Devi or Vishahara (‘the destroyer of poison’), the subject of Kaiser Haq’s The Triumph of the Snake Goddess (Harvard University Press, 2015), with an introduction by Wendy Doniger (the very same). The point is, whether about Krishna, Manasā or Sukanya, oftentimes these stories have no one definitive text. Or wider appreciation. It took his mother-in-law Parvati Rajan to alert Ravi Shankar even to this story’s existence. Traditional tales like these could be likened, in a manner of speaking, to a quiver full of variants. An individual arrow may come with a pre-modern arrowhead but can hit a modern target when fletched differently. That is what Ravi Shankar was aiming for with Sukanya.